Wonder

Sermon Delivered at The Local Church

February 11, 2024 • Transfiguration Sunday

Scripture: Luke 9:28–36

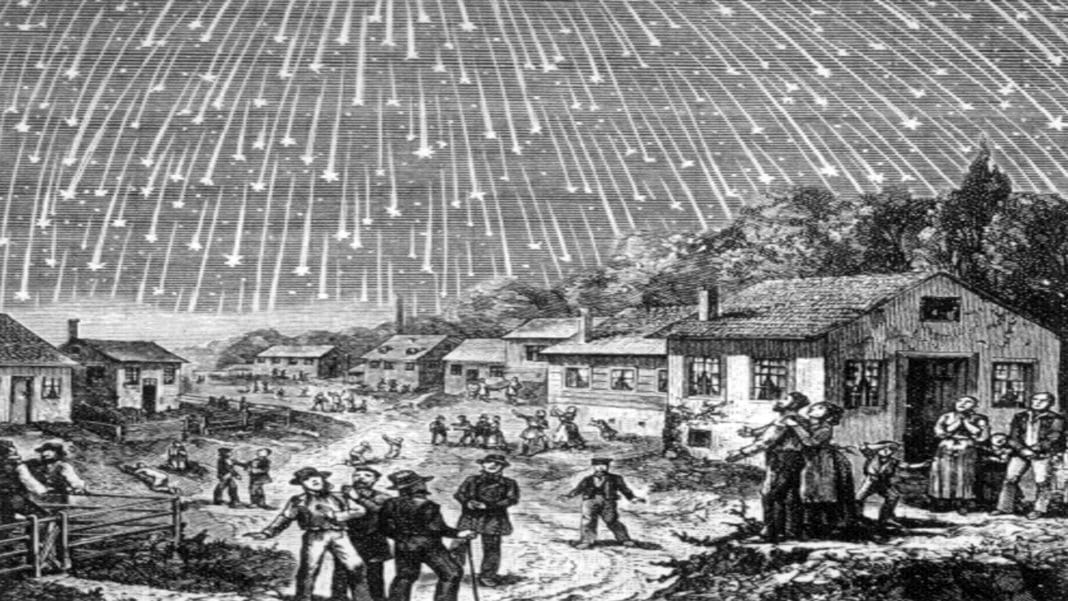

If you happened to live along the East Coast of the United States and found yourself awake and outdoors in the early morning hours of November 13, 1833, you wouldn’t have believed your eyes. You would have seen what the New York Evening Post described as “a shower of fire” — shooting stars in numbers that you would have thought, as they did, that “the planets and constellations were falling from their places.”

This phenomenon, unlike any they’d ever experienced at this scale, illuminated their night and shone all around them — stars seeming to fall with such intensity and magnitude that many expected their homes to catch fire. The Baltimore Patriot newspaper declared it “one of the most grand and alarming spectacles which ever beamed into the eye of man.”

For some, it caused panic. For others, it was a fulfillment of prophecy. For others still, it was the cause of awe and wonder at the celestial spectacle.

They couldn’t explain then what we know now to be true — that this was the result of the annual Leonid meteor shower. It happens every November or so when the Earth passes through the debris left by the Tempel-Tuttle comet. In fact, it was some early crowdsourcing in the wake of this experience that led some resourceful scientists to begin to realize this was part of an annual event.

This night would come to be known as the Night the Stars Fell, and can you imagine what it would’ve been like — with no frame of reference — to look up and see the sky on fire? To witness shooting stars by the thousands? To marvel at the inexplicable?

And, sure, we now have an explanation. But who among us doesn’t still stop in our tracks when we see a shooting star? Who among us doesn’t, however briefly, exit our quotidian mundanity to marvel at something so rare? So beautiful? Beyond the explanations, beyond the understanding, it still feels a little like magic.

Today’s scripture passage hits on many of these themes — unexplained spectacles, all-consuming wonder, the fulfillment of prophecy perhaps, illumination at every turn. And we’ll get there in just a moment.

But first, as we begin, let’s be quiet for a moment…

Today marks a turning point in many ways. In our liturgical calendar, the calendar that shapes the church year, today is Transfiguration Sunday. We hear this story of Jesus’s Transfiguration every year on the final Sunday of the season of Epiphany, which we’ve been in since early January, and the Sunday before the season of Lent, which starts this Wednesday with Ash Wednesday. We’ll share more about Lent throughout the week.

But it’s a turning point not only because this bizarre mountaintop story is a hinge between Epiphany and Lent but also because it marks a turning point for Jesus. To this point, Jesus has been traveling from place to place, preaching liberation, deliverance, and Jubilee… and then actually making it real by healing persons with leprosy, calming storms, casting out demons, feeding the five thousand. He’s doing the thing. But after this mountaintop experience, as he leads Peter, James, and John down the mountain, Jesus will set his face to Jerusalem and the fate that awaits him — his crucifixion and death. So it’s a turning point in that respect, too.

But before we get too far ahead of ourselves, let’s set the scene here.

Jesus tells three of his disciples, “Hey Peter, James, John, let’s go.” And so they do. And what you’ve got to remember is that they haven’t stopped. The disciples — Jesus’s closest friends and followers, have been traveling with Jesus for much of his ministry, moving from place to place. Where he goes, they go. And now, while the others get to hang back and kick their feet up, Jesus says, “Come on. We’re going up that mountain to pray.”

You can imagine the blisters on their feet or that feeling of your legs becoming tree trunks. The bottom line is that they’re very likely exhausted. Luke even says as much when he points out that they were “weighed down with sleep” once they reached the top. There’s every chance in the world that they’re doing that thing where they’re trying to stay awake by switching which eye is open to give the other one a chance to rest. Have you ever done that?

So they get to the top, and Jesus goes to pray — when all of a sudden, his face changes, and his clothes become dazzling white. “As bright as a flash of lightning,” Luke says. Jesus is transfigured right there before them. He doesn’t just look a little different. Everything changes. His face. His clothes. Everything.

And then, as if that’s not wild enough, Moses and Elijah appear representing the Law and the Prophets — these giants of the faith, those who, according to Jewish tradition, were still alive in the presence of God. And they’re just having a conversation, talking about Jesus’s exodus, his departure. And we’re unsure whether that means his departure from the mountain or his exodus from this earth. And if it’s the latter, then we might hear echoes of liberation and deliverance there, echoes of Jubilee, harkening back not only to Jesus’s inaugural sermon in Nazareth described in Luke 4 but also to the Book of Exodus in the Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible, in which God’s people were delivered from slavery into the Promised Land.

Peter, James, and John rub their eyes a few times because they can’t believe what they’re seeing, and maybe it’s the terror, or perhaps it’s the exhaustion, or who knows, but Peter, always quick to speak, says this:

Just as they were leaving him, Peter said to Jesus, “Master, it is good of run to be here; let us set up three tents: one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah,” not realizing what he was saying (Luke 9:33).

In other words, Peter’s like, “Why don’t we pitch some tents and hang out for a little bit?” Why don’t we make this last a little longer? Perhaps he wanted to take control of the situation.

But then, because, of course, it can only get weirder, a cloud appears, overshadows them, consumes them — and from the cloud comes a voice that echoes the words spoken at Jesus’s baptism:

Then from the cloud came a voice that said, “This is my Son, my Chosen; listen to him!” (Luke 9:35)

And no sooner does the voice speak than it’s all over. Just like that, there’s no cloud. No Moses. No Elijah. Just Jesus and Peter and James and John. The disciples are left in stunned silence. Here’s the next verse.

When the voice had spoken, Jesus was found alone. And they kept silent and in those days told no one any of the things they had seen. (Luke 9:36)

It’s bonkers.

And goodness, I love Peter. I relate so much to him. The dude wears his heart on his sleeve. He’s always the first to speak (as is the case here)—even if it hasn’t been fully thought out. My dad would always tell me, “Think before you speak.” The only reason he had to tell me so much was because I often didn’t—and still don’t.

For instance, in the passage from last week, Peter is the first to speak when Jesus asks who the disciples say he is. It’s Peter who wants a full body wash when Jesus is washing his disciples’ feet. It’s Peter who wants to argue with Jesus when Jesus talks about his fate — about his death. It’s Peter who cuts off a guy’s ear in defense of Jesus when he’s betrayed and arrested. And when push comes to shove, it’s Peter who denies knowing Jesus three times in the run-up to the crucifixion. Peter’s all over the place.

I love him so much because I can relate to him. I feel it. And yet, it’s interesting, isn’t it, that when coming down the mountain, Peter, along with the others, keeps silent.

And now, you might be wondering, “Okay, but what does it mean? Explain it to me. Help me understand it.” And sure. After all, isn’t it my job to tell you what it means so that you can apply it to your life and come back next week for more? I could do that. I have done that. (I will still probably do that.)

But, at least for a little while, I want us to wonder what it might have been like — with no frame of reference — to look up and see the sky seemingly on fire with light and Jesus, wrapped in glory, in the midst of it. To witness stars of the Jewish faith, Moses and Elijah, standing before you. To marvel at the inexplicable notion of an all-consuming cloud and a voice from heaven?

And with that, I want us also to wonder why the disciples kept silent.

Because you better believe that if it were me, I would’ve been asking Jesus those same questions. What does it mean? Was that really Moses and Elijah? How did you do that? I want that knowledge.

But instead, they kept silent. Because perhaps they were processing. Wondering.

And so here’s what I want to lift up this morning. It seems to me that we’ve been programmed a certain way. The world has lost its magic. We’ve been conditioned to believe, despite our protests to the contrary, perhaps, that this is all there is. Even if we claim otherwise, so often, our actions — my actions — tell a different story.

Here, in post-enlightenment modernity, knowledge is power. We are thirsty for information. We want explanations. We want answers. Our world is driven by ones and zeros, data, and algorithms. There’s no room for mystery. No room for curiosity. No room for wonder. The world has been drained of enchantment, and this is how we’ve been conditioned.

This plays out in several areas of our lives. If you have a question, ChatGPT or any of our virtual assistants, like Siri or Alexa, would be happy to answer it. What year did the first Star Wars come out? Who invented Legos? Can Taylor Swift make it to the Super Bowl in time from the Eras Tour?

But none of these questions get to how you felt when you heard Princess Leia’s theme for the first time, when you placed the final Lego on the project you’d been working on with your kid, or when you experienced the ecstasy of singing Cruel Summer with tens of thousands of others.

Think also about how this disenchantment functions in politics. Drained of curiosity and wonder, we’re seduced into snap judgments. You’re either with us or against us. If you vote a certain way or support a certain candidate, then I immediately know everything about you—filling in the gaps on my own without the possibility that you might be human, with complexity, surprise, and a story.

And the church has done this, too. We’re not immune. And I think it’s why so many have walked away from the faith, seeing it as outdated and irrelevant — because for too long, the message has been that we have it all figured out, and so if you want to join, you need to agree to the terms, sign on the dotted line, and you're good to go. Otherwise, sorry. Just believe my understanding of things. But that’s not faith at all.

Because, as St. Augustine famously put it:

“If you can understand it, it’s not God.”

Where’s the beauty in this if it’s only about regurgitating facts? Where’s the mystery? Where’s the magic?

So what if it’s not about understanding it? Because here’s the thing: If we understand something and can explain it, then we can control it. And if we can control it, it can't work on us. It can't change us. It can't transfigure us.

I remember one night Natalie and I were having dinner years ago, and she asked a question — I don’t remember what it was — but I pulled my phone out to Google the answer. And before I could type anything in, she said, “I wasn’t asking. I was just wondering.”

When was the last time you just let yourself wonder?

And that’s why I love that the disciples walk down the mountain in silence. Because for a brief moment, Peter, James, and John exited their quotidian mundanities to marvel at something rare. Something beautiful. Something that defied expectations and understanding. Something that felt a little like magic in a world that seemed drained of it.

And so I’ve got to believe that they’re wondering, too. Their world has just been turned on end and broken open. And perhaps they’re wondering that if this transfiguration is possible, what other transfigurations might God make possible? Maybe this Jesus is who he says he is. Maybe hope isn’t so elusive. Maybe their own salvation, their own exodus, is near. What else might God make possible? In lives that feel so heavy? In a world that feels so unjust? In the longings they felt deep in their bones? What other transfigurations might God make possible?

I know that many of us are running on empty. This week, I heard someone describe our present era as “The Age of Anxiety,” which feels so apt. I don’t know about you, but I can feel the year ramping up and our calendars thickening with spring sports, college visits, due dates, planned travel to see the grandkids, and everything else. And it will be easy to fall back into routines and rhythms devoid of wonder — just moving from one thing to the next on the great conveyor belt of life.

And I could tell you today what I think this story means. I could explain it. I could talk about how we often have mountaintop moments, but we can’t stay there. About how there’s still work to be done, and God is with us as we go. Or about how Jesus’s exodus is the promised deliverance of God’s people from oppression and all that has held them captive. And that means our deliverance is in his hands, too. Or about how this event affirms Jesus’s identity such that we’re compelled to follow him into the shadow of death to our own glory, but we don’t go without that blessing of belovedness.

I could do that. I could tell you what it means. But I won’t. Because, at least today, I’m not sure this story is intended to be understood as much as it is to be experienced.

What if we’re not supposed to torture a confession out of this story but instead simply to marvel at what God can do? Because if this is possible, then by God’s grace, other seemingly impossible things — things that feel like magic — might be possible, too.

Seemingly impossible things like forgiveness in a culture of ungrace. Generosity in a world of scarcity. Healing when the grief is thick. Wholeness when you feel so scattered. Wonder when we’ve been programmed toward disenchantment. Seemingly impossible things like resurrection in the midst of death.

“Earth’s crammed with heaven,” the poet, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, wrote. “And every common bush afire with God. But only he who sees takes off his shoes…”

As we stand at this turning point between Epiphany and Lent, between where we’ve been and where God is calling us to be, the invitation over the next few weeks as we journey toward the heartbreak and hope of Holy Week and Easter is to give ourselves over to what God might do in us — to move from control and tight fists to open palms — ready to receive with wonder our own transfigurations and that of the world around us.

So, friends, here’s my prayer for you.

If you’ve grown weary like the disciples journeying up the mountain, I pray that you’ll know your slog is not in vain and that Jesus goes with you, God’s grace is ahead of you, and something that takes your breath away might be just up ahead.

If the possibility of change has felt elusive, whether that’s a longing in you or hope for someone you love, I pray you’ll trust that the God who can transfigure Jesus can do the same in that person, in that relationship, in that situation that you hold in your heart right now.

If you’ve become disenchanted with the way of the world, and the colors have grown dull, or if you’ve felt pressure to have it all figured out, I pray that you’ll take off your shoes so that God might rekindle in you a sense of awe and wonder and grant you anew a childlike faith to see the magic that is all around.

And if the road ahead feels daunting, if your journey down the mountain feels treacherous, then I pray that as you follow Jesus to the other side, you’ll know that those same words of belovedness and blessing spoken over Jesus are for you, too — grace for your journey as you put one foot in front of the other.

In the name of God: Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer, Amen.